Author: Thom Holwerda

Source

Sponsored:

Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence - Audiobook

Uncover the true cost of artificial intelligence.

Listen now, and see the system behind the screens before the future listens to you. = > Atlas of AI $0.00 with trial. Read by Larissa Gallagher

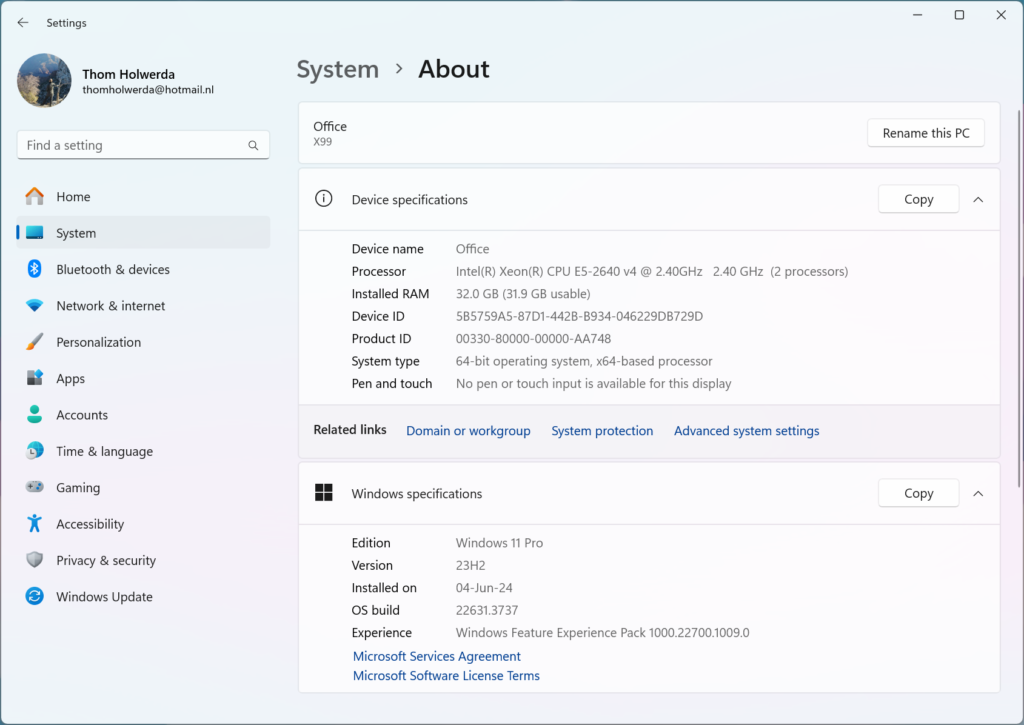

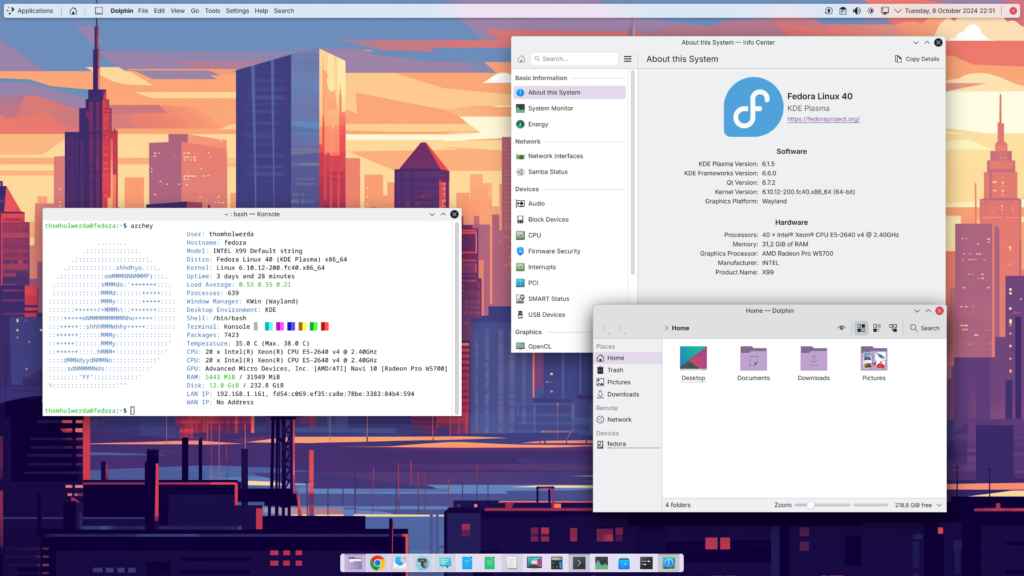

It should be no secret to anyone reading OSNews that I’m not exactly a fan of Windows. While I grew up using MS-DOS, Windows 3.x, and Windows 9x, the move to Windows XP was a sour one for me, and ever since I’ve vastly preferred first BeOS, and then Linux. When, thanks to the tireless efforts of the Wine community and Valve gaming on Linux became a boring, it-just-works affair, I said goodbye to my final gaming-only Windows installation about four or so years ago. However, I also strongly believe that in order to be able to fairly criticise or dislike something, you should at least have experience with it. As such, I decided it was time for what I expected was going to be some serious technology BDSM, and I installed Windows 11 on my workstation and force myself to use it for a few weeks to see if Microsoft’s latest operating system truly was as bad as I make it out to be in my head. Installing Windows 11 Technically speaking, my workstation is not supported by Windows 11. Despite packing two Intel Xeon E5 V4 2640 CPUs for a total of 20 cores and 40 threads, 32 GB of ECC RAM, an AMD Radeon Pro w5700, and the usual stuff like an M.2 SSD, this machine apparently did not meet the minimum specifications for Windows 11 since it has no TPM 2.0 security chip, and the processors were deemed too old. Luckily, these limitations are entirely artificial and meaningless, and using Ventoy, which by default disables these silly restrictions, I was able to install Windows 11 just fine. During installation, you run into the first problem if you’re coming from a different operating system – even after all these years, Windows still does not give a single hootin’ toot about any existing operating systems or bootloaders on your machine. This wasn’t an issue for me since I was going to allow Windows to take over the entire machine, but for those of used to have control over what happens when we install our operating systems, be advised that your other operating systems will most likely be rendered unbootable. The tools you have access to during installation for things like disk partitioning are also incredibly limited, and there’s nothing like the live environments you’re used to from the Linux world – all you get is an installer. In addition, since Windows only really supports FAT and NTFS file systems, your existing ext4, btrfs, UFS, or ZFS partitions used by your Linux or BSD installs will not work at all in Windows. Again – be advised that Windows is a very limited operating system compared to Linux or BSD. Once the actual installation part is done, you’re treated to a lengthy – and I truly mean lengthy – out of box experience. This is where you first get a glimpse of just how much data Microsoft wants to collect from its Windows users, and it stands in stark contrast to what I’m used to as a Linux user. On my Linux distribution of choice, Fedora KDE, there’s really only KDE’s opt-in, voluntary User Feedback option, which only collects basic system information in an entirely anonymous way. Windows, meanwhile, seems to want to collect pretty much everything you do on your machine, and while there’s some prompts to reduce the amount of data it collects, even with everything set to minimum it’s still quite a lot. Once you’re past the out of box experience, you can finally start using your new Windows installation – but actually not really. Unlike a Linux distribution, where all your hardware is detected automatically and will use the latest drivers, on Windows, you will most likely have to do some manual driver hunting, searching the web for PCI and vendor IDs to hopefully locate the correct drivers, which isn’t always easy. To make matters worse, even if Windows Update installs the correct drivers for you, those are often outdated, and you’re better off downloading the latest versions straight from the vendors’ websites. This is especially problematic for motherboard drivers – motherboard vendor websites often list horribly outdated drivers. Updating Windows 11 Once you have all the drivers installed and updated, which often requires several reboots, you might notice that your system seems to be awfully busy, even when you’re not actually doing anything with it. Most likely, this means Windows Update is running in the background, sucking up a lot of system resources. If you’re used to Linux or BSD, where updating is a quick and centralised process, updating things on Windows is a complete and utter mess. Instead of just updating everything all at once, Windows Update will often require several different rounds of updates, marked by reboots. You’ll also discover that Windows Update is not only incredibly slow both when it comes to downloading and installing, but that it’s also incredibly buggy. Updates will randomly fail to install for no apparent reason, and there’s a whole cottage industry of useless ML and SEO content on the internet trying to “help” you fix these issues. On my system, without doing anything, Windows Update managed to break itself in less than 24 hours – it listed 79 (!) driver updates related to the two Xeon processors (I assume it listed certain drivers for every single of the 40 threads), but every single one of them, save for one or two, would fail to install with a useless generic error code. Every time I tried to install them, one or two more would install, with everything else failing, until eventually the update process just hung the entire system. A few days later, the listed updated just disappeared entirely from Windows Update. The updates had no KB numbers, so it was impossible to find any information on them, and to this day, I have no idea what was going on here. Even after battling your way through Windows Update, you’re not done actually updating your system. Unlike,