Author: Thom Holwerda

Source

Sponsored:

Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence - Audiobook

Uncover the true cost of artificial intelligence.

Listen now, and see the system behind the screens before the future listens to you. = > Atlas of AI $0.00 with trial. Read by Larissa Gallagher

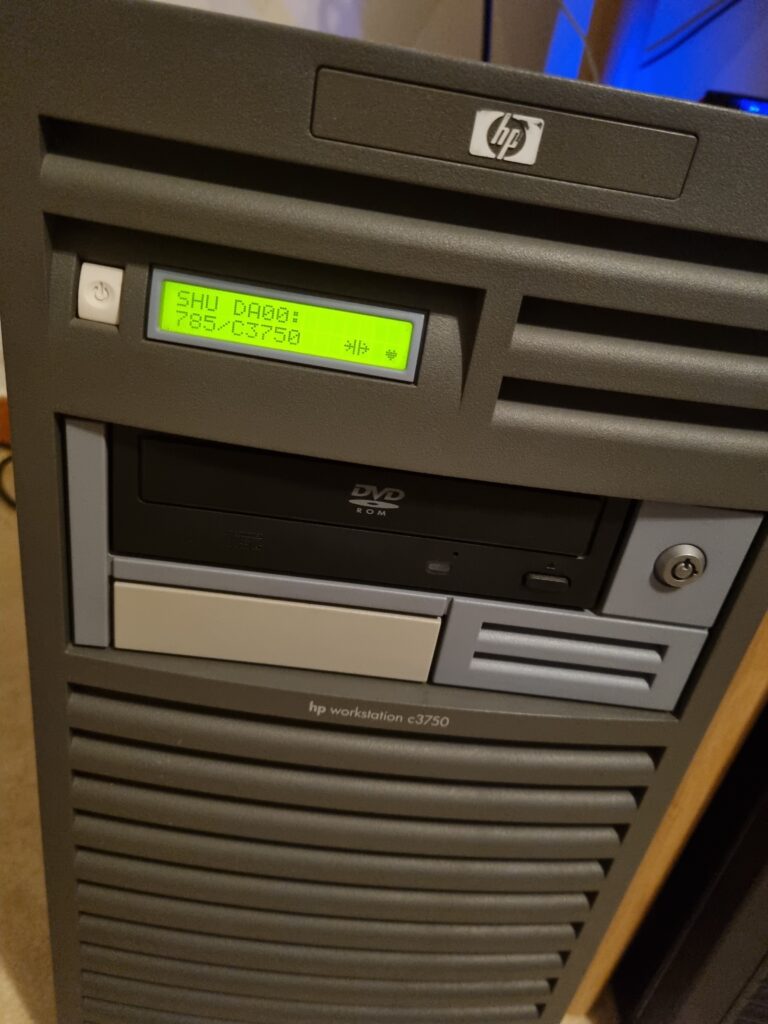

Back in the ’90s and very early 2000s, a whole market segment of computers existed that we don’t really talk about anymore today: the UNIX workstation. They were non-x86 machines running one of the many commercial UNIX variants, and were used for the very high end of computing. They were expensive, unique, different, and quite often incredibly overengineered. Countless companies made and sold these UNIX workstation. SGI was a big player in this market, with their fancy, colourful machines with MIPS processors running IRIX. There was also Sun Microsystems (and Oracle in the tail end), selling ever more powerful UltraSPARC workstations running Solaris. Industry legend DEC sold Alpha machines running Digital UNIX (later renamed to Tru64 UNIX when DEC was acquired by Compaq in 1998). IBM of course also sold UNIX workstations, powered by their PowerPC architecture and AIX operating system. As x86 became ever more powerful and versatile, and with the rise of Linux as a capable UNIX replacement and the adoption of the NT-based versions of Windows, the days of the UNIX workstations were numbered. A few years into the new millennium, virtually all traditional UNIX vendors had ended production of their workstations and in some cases even their associated architectures, with a lacklustre collective effort to move over to Intel’s Itanium – which didn’t exactly go anywhere and is now nothing more than a sour footnote in computing history. Approaching roughly 2010, all the UNIX workstations had disappeared. Development of MIPS, UltraSPARC (for workstations), Alpha, and others had all been wound down, and with a few exceptions, the various commercial UNIX variants started to languish in extended support purgatory, and by now, they’re all pretty much dead (save for Solaris). Users and industries moved on to x86 on the hardware side, and Linux, Windows, and in some cases, Mac OS X on the software side. I’ve always been fascinated by these UNIX workstations. They were this mysterious, unique computers running software that was entirely alien to me, and they were impossibly expensive. Over the years, I’ve owned exactly one of these machines – a Sun Ultra 5 running Solaris 9 – and I remember enjoying that little machine greatly. I was a student living in a tiny apartment with not much money to spare, but back in those days, you couldn’t load a single page on an online auction website without stumbling over piles of Ultra 5s and other UNIX workstations, so they were cheap and plentiful. Even as my financial situation improved and money wasn’t short anymore, my apartment was still far too small to buy even more computers, especially since UNIX workstations tended to be big and noisy. Fast forward to the 2020s, however, and everything’s changed. My house has plenty of space, and I even have my own dedicated office for work and computer nonsense, so I’ve got more than enough room to indulge and buy UNIX workstations. It was time to get back in the saddle. But soon I realised times had changed. Over the past few years, I have come to learn that If you want to get into buying, using, and learning from UNIX workstations today, you’ll run into various problems which can roughly be filed into three main categories: hardware availability, operating system availability, and third party software availability. I’ll walk through all three of these and give some examples that I’ve encountered, most of them based on the purchase of a UNIX workstation from a vendor I haven’t mentioned yet: Hewlett Packard. Hardware availability: a tulip for a house The first place most people would go to in order to buy a classic UNIX workstation is eBay. Everyone’s favourite auction site and online marketplace is filled with all kinds of UNIX workstations, from the ’80s all the way up to the final machines from the early 2000s. You’ll soon notice, however, that pricing seems to have gone absolutely – pardon my Gaelic – absolutely batshit insane. Are you interested in a Sun Ultra 45, from 2005, without any warranty and excluding shipping? That’ll be anywhere from €1500 to €2500. Or are you more into SGI, and looking to buy a a 175 Mhz Indigo 2 from the mid-’90s? Better pony up at least €1250. Something as underpowered as a Sun Ultra 10 from 1998 will run for anything between €700 and €1300. Getting something more powerful like an SGI Fuel? Forget about it. Going to refurbishers won’t help you much either. Just these past few days I was in contact with a refurbisher here in Sweden who is charging over €4000 for a Sun Ultra 45. For a US perspective, a refurbisher like UNIX HQ, for instance, has quite a decent selection of machines, but be ready to shell out $2000 for an IBM IntelliStation POWER 285 running AIX, $1300 for a Sun Blade 2500, or $2000-$2500 for an SGI Fuel, to list just a few. Of course, these prices are without shipping or possible customs fees. It will come as no surprise that shipping these machines is expensive. Shipping a UNIX workstation from the US – where supply is relatively ample – to Europe often costs more than the computer itself, easily doubling your total costs. On top of that, there’s the crapshoot lottery of customs fees, which, depending on the customs official’s mood, can really be just about anything. I honestly have no idea why pricing has skyrockted as much as it has. Machines like these were far, far cheaper only 5-10 years ago, but it seems something happened that pushed them up – quite a few of them are definitely not rare, so I doubt rarity is the cause. Demand can’t exactly be high either, so I doubt there’s so many people buying these that they’re forcing the price to go up. I do have a few theories, such as some machines being absolutely required in some specific niche somewhere and sellers just sitting on them until one breaks and must be replaced, whatever the cost,